Lindsey Graham’s disturbing comments about investigating Biden

(CNN)Sen. Lindsey Graham stated on CBS News on Sunday morning that Attorney General William Barr has set up a mechanism to receive purportedly damaging information coming from Ukraine, via Rudy Giuliani, about former Vice President (and current Democratic presidential contender) Joe Biden and his son Hunter Biden.

There would be so many things wrong with Barr granting VIP direct access to Giuliani that it’s hard to know where to start.

First, Giuliani is treading in murky waters, at best, by continuing to solicit campaign dirt from foreign nationals to be used against Biden — and now Barr reportedly has plunged himself and the Justice Department right into that same mire by openly accepting, and weaponizing, the anti-Biden (hence, pro-Trump) dirt that Giulani generates. The Senate did not convict Trump for his conduct toward Ukraine — though even some of Trump’s Republican defenders noted that his actions were inappropriate — but it remains a federal crime to “solicit, accept, or receive” a campaign contribution or donation — defined as “money or other thing of value” — from a foreign national.

The Justice Department has, however, refused even to open an investigation of the efforts of Trump and his surrogates to gather (or generate) dirt from Ukrainians on the Bidens. The President has repeatedly made unfounded and false claims to allege that the Bidens acted improperly in Ukraine.

There is no evidence of wrongdoing by either Joe or Hunter Biden. It is an unresolved legal issue whether election “dirt” qualifies legally as a thing of value, but former Federal Election Commission counsel Larry Noble argues persuasively that it should. It is wildly irresponsible for Barr to countenance and encourage such borderline (at best) and illegal (at worst) conduct.

Second, Barr, if the arrangement indeed exists, would once again reveal himself to be a spineless partisan, serving Trump’s every political and personal desire. In the year he has spent in office as the nation’s top prosecutor, Barr already has distorted in Trump’s favor the findings of special counsel Robert Mueller; publicly echoed Trump’s non-legal, campaign catch phrases like “no collusion” and that his campaign was subject to “spying“; and his DOJ tried to prevent the Ukraine whistleblower’s complaint from going to Congress, as required by law.

Simply put, Barr has not taken a single move during his first year in office that would in any way undermine Trump’s political wishes, but he has bent the law and common sense in Trump’s favor at every turn.

Finally, let’s not forget: Rudy Giuliani himself is reportedly under criminal and counterintelligence investigation by the Southern District of New York (which is part of the Justice Department). The arrangement Graham describes would present conflicts of interest in both directions.

Giuliani has every incentive to ingratiate himself with Barr by taking steps perceived as favorable to Barr or his benefactor, Trump. And, by giving Giuliani special access to the head of the Justice Department, Barr would be creating real questions about his impartiality in assessing a potential criminal charge against Giuliani. Beyond that, just as a basic matter of common sense: How smart would it be for an attorney general to open a direct line of communication with a potential counterintelligence threat?

Graham spoke of this new pipeline of information from Giuliani to Barr as if it was a good thing, as if it will somehow clean up corruption. That notion is laughable. If anything, the Giuliani-Barr connection itself would be a manifestation of the worst kind of corruption — where the attorney general acts not as the top lawyer and prosecutor for the people of the United States, but rather as the President’s most enthusiastic and unprincipled political cheerleader.

Now, your questions:

Dave (Minnesota): Is there double jeopardy in an impeachment? If new information comes to light, can Trump be impeached again?

Double jeopardy — the principle that a person cannot be charged twice for the same offense — applies to criminal charges but not to impeachment. The Fifth Amendment of the Constitution provides that no person shall “be subject for the same offense to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb.” The phrase “life or limb” refers to physical punishment such as incarceration or execution. The penalty for impeachment — removal from office — is fundamentally different and does not qualify as loss of “life or limb.”

While an official legally can be impeached more than once, there are political obstacles to a second impeachment. Impeachment is commonly seen as a politically divisive process. And, while Trump was the 20th American official to be impeached by the House, no American official ever has been impeached multiple times.

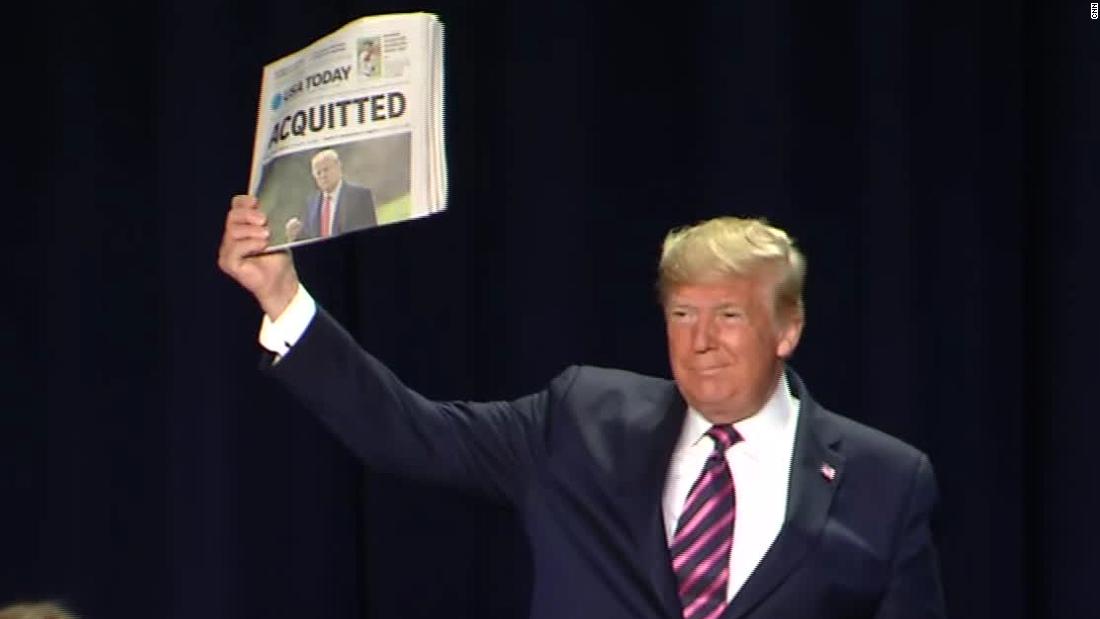

All things considered, there is virtually no chance the House impeaches Trump again based on the Ukraine scandal, even if new evidence emerges. If an entirely separate scandal should emerge at some point, a second impeachment could be more politically palatable, but still would be tempered politically by the fact that Trump already has been impeached, and acquitted, once.

Barbara (Michigan): Does the acquittal of President Trump mean that the President is above the law?

No, the acquittal of Trump does not place the President above the law, but it does fundamentally alter the balance of powers in favor of the presidency.

By constitutional design, impeachment is rare and conviction is rarer still. The Constitution permits impeachment only for “treason, bribery or other high crimes and misdemeanors” and requires a supermajority two-thirds vote in the Senate to convict and remove. There has been, on average, fewer than one impeachment per decade over our history — and only eight of the officials impeached have been tried and convicted.

The Trump impeachment has altered the balance of powers between the branches of government in two crucial respects. First, some of Trump’s defenders, including several senators who voted to acquit, argued that Trump’s conduct, even if wrong or improper, was not impeachable. While one impeachment is not legally binding on future impeachments, if the Trump standard is followed, it will become more difficult — perhaps near impossible — to impeach and remove an official based on abuse of power.

Second, Trump essentially got away consequence-free with defying all congressional subpoenas relating to the Mueller inquiry and the impeachment investigation and trial, making good on his public vow that “we’re fighting all the subpoenas.” White House counsel Pat Cipollone later openly defied Congress, writing to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi that Trump “reject[s] your baseless, unconstitutional efforts to overturn the democratic process” and would not comply with any requests for information.

So the bottom line, for now, is that the House served dozens of subpoenas; Trump defied every one of them; and with his acquittal there seems to be no negative consequence to that refusal. If that result stands, it will severely impair the ability of Congress to conduct oversight of the President and the executive branch. Congress still has the option to go to court to enforce future subpoenas should the administration continue to stonewall.

But unless and until the courts resolve the issue in favor of Congress, the executive branch has effectively diminished one of Congress’s most important checks on the President.

Roger (Wisconsin): Was it a mistake for House Democrats to impeach Trump based on abuse of power, without a specific crime?

History and the law make clear that impeachment need not be based on a specific statutory crime. Indeed, federal officials have been impeached for noncriminal abuses of power or misconduct ranging from “favoritism” to “intoxication.” The House was well within the law, therefore, to impeach Trump for two noncriminal acts: “Abuse of Power” (Article I) and “Obstruction of Congress (Article II).

The House did not need to — but could have — also impeached based on specific statutory crimes including bribery, extortion and solicitation of foreign election aid. House Democrats could have alleged these crimes as sub-parts of the abuse of power article of impeachment, or as separate articles after the abuse of power allegation.

We do not know precisely why House Democrats opted against alleging specific crimes. My best guess is they did not want to get drawn into a complex, legalistic debate about the nuances of the elements required to prove a statutory crime. Instead, they opted for the broader, more sweeping Abuse of Power allegation.

But by deciding not to allege specific crimes, House Democrats opened the door to the rhetorical argument that the impeachment was somehow lacking — as Trump himself put it, “impeachment lite.”

Trump’s defense team amplified this theme during trial, arguing that in the absence of a criminal (or “criminal type”) allegation, the impeachment must fail. Had House Democrats alleged specific crimes, they would have preempted this line of defense.

Sign up for CNN Opinion’s new newsletter.

Three questions to watch:

1. Will the House subpoena John Bolton and other witnesses on the Ukraine scandal?

2. What will happen on the various emoluments clause lawsuits against President Trump, now that the DC Circuit Court of Appeals has ruled in Trump’s favor in one such suit?

3. Will President Trump seek retribution against other witnesses, beyond Lt. Col. Vindman and Ambassador Gordon Sondland?

Read more: https://www.cnn.com/2020/02/09/opinions/lindsey-graham-doj-barr-biden-investigation-honig/index.html